From Persia to Iran: Distortion of the 1935 "Name Change"

How Western commentators have misrepresented Reza Shah’s aim—and why the truth about Iran’s identity matters.

By Banafsheh Zand

On March 21, 1935, coinciding with Nowruz, the Persian New Year, Reza Shah Pahlavi formally requested that foreign governments refer to his country by its indigenous name: Iran. What might appear to outsiders as a minor semantic correction was, in truth, a bold assertion of national sovereignty and identity. It was a symbolic act with deep historical roots, political undertones, and enduring cultural implications.

For centuries, “Persia” had been the name used by the outside world, a term originating from Greek references to the southwestern province of Pars (Fars), the heartland of the ancient Achaemenid Empire. Internally, however, the name “Iran”—meaning “Land of the Aryans”—had long held cultural and historical significance. It was embedded in Zoroastrian scriptures, Middle Persian inscriptions, and later immortalized in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. By insisting on the name “Iran,” Reza Shah was not inventing a new identity but reviving a buried one.

Reza Shah’s rise to power in 1925 marked the beginning of an era of ambitious modernization. Inspired in part by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey, Reza Shah launched a sweeping set of reforms aimed at centralizing authority, secularizing education, developing infrastructure, and standardizing law. The name change from Persia to Iran was an extension of this same reformist zeal: it sought to align the country’s external label with its internal self-conception, while also distancing Iran from the decadence and weakness associated with Qajar-era “Persia.”

Letter from Knatchbull-Hugessen mocking the Iranian request to adopt the name 'Iran' (28 December 1934).

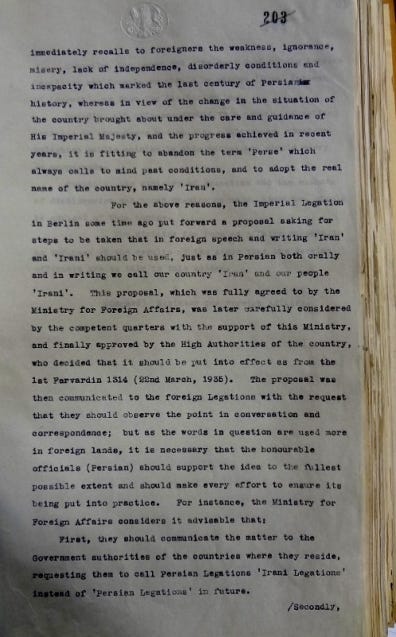

In official correspondence, Iran’s government made clear that this was not simply a stylistic change, but a rectification of what they termed an “etymological and historical inexactitude.” They asserted that the continued use of “Persia” evoked foreign-imposed associations of “weakness, ignorance, misery, lack of independence, disorderly condition and incapacity”—a damning portrait of the 19th century that Reza Shah’s regime had struggled to erase.

The request also extended to titles. The Shah insisted on being referred to as Sháhinsháh—King of Kings—a revival of a pre-Islamic designation rich in imperial symbolism. Foreign officials, particularly the British, were less than impressed.

Memo detailing the British Foreign Office’s translation approach to Persian governmental titles.

The British Foreign Office’s reaction ranged from bemused condescension to outright ridicule. In a 1933 memorandum, Oriental Secretary C.G. Trott acknowledged that the Persians were entitled to choose their own appellations. Yet the internal notes betrayed a tone of cultural superiority. One official joked about translating the full British state title in return, while another quipped about “swallowing the camel and straining at the gnat” over the circumflex in “Irân.”

Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, the British Minister in Tehran, wrote disdainfully in 1934 that “we have just received an absurd note” from the Iranian government requesting the use of “Iranian” instead of “Persian.” He blamed Herodotus for the original naming error and sardonically added that the request seemed to come from a desire to disown the Arab elements of the country’s history.

Circular from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs defending the change from 'Persia' to 'Iran'.

Some Foreign Office members even worried the name change might signal a claim to rename the Persian Gulf, or complicate British commercial operations—such as renaming the Anglo-Persian Oil Company or the Imperial Bank of Persia. There were practical anxieties as well, including confusion with neighboring Iraq and complications in military mapping and public correspondence.

Eventually, the British conceded. Though they continued to use “Persia” informally and in internal communications well into the 1950s, formal diplomatic references adopted the name “Iran.” As one 1952 report noted, the Shah had finally agreed that “Persia” and “Perse” could still be used in foreign languages—just not by Iranians when speaking them.

Churchill’s 1941 minute suggesting 'Persia' be used to avoid confusion with 'Iraq'.

One of the most fascinating visual symbols of the change came in the form of postage stamps. Prior to 1935, Iranian stamps typically bore the inscription “Persia” or “Perse,” especially since French was the international language of postal services. Following the official name change, existing stamp stocks—such as the 1929 series featuring Reza Shah—were overprinted with “POSTES IRANIENNES.”

Soon, entirely new issues were released, marked with “Iran” in both Persian and French. These stamps depicted the Shah alongside factories, railways, and ancient monuments—a visual narrative of a state reaching toward modernity while rooted in imperial glory. In these small, tangible artifacts, one sees the ideological marriage of past and future that underpinned Reza Shah’s vision.

Trott’s 1933 memo suggesting options for how Britain could respond to Iran’s naming demands.

In recent years, the name change has been misrepresented and distorted, most infamously by French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, as can be seen in the below video. He has argued that Reza Shah renamed Persia to Iran to curry favor with Nazi Germany, referencing the shared use of the word “Aryan.” This interpretation is not only anachronistic; it is downright misleading.

First, the name “Iran” predates Nazism by millennia and had been in domestic use ages before the Nazis emerged. It appears in Zoroastrian texts, Sassanian inscriptions, and the Persian literary canon.

A British marginal note criticizing the circumflex in the name 'Irân'.

Second, Reza Shah’s reforms were far more aligned with Kemalist secularism than Hitler’s racial ideology. His drive for modernization, unveiling of women, secular education, and industrial development bear no resemblance to the fascist policies of 1930s Germany.

Third, the overprints and official rebranding were primarily in French, not German, which would be odd if the goal was Nazi appeasement. Diplomatic and philatelic communication targeted the global Francophone audience, particularly international postal systems and bureaucracies.

Internal British reaction satirizing the name 'Irania' and the volume of discussion.

Finally, while Iran did conduct trade with Germany in the 1930s—as did Britain and other powers—Reza Shah was not ideologically beholden to Hitler. His eventual abdication in 1941, forced by a joint British-Soviet invasion, demonstrates the limits of his geopolitical balancing act.

The transformation from Persia to Iran was not a capitulation to foreign powers or a flirtation with fascism. It was, at its core, a deliberate, sovereign choice—a way for a modernizing state to define itself on its own terms. In postal stamps and foreign policy, in formal titles and everyday parlance, “Iran” stood for a country reclaiming its narrative.

Persian government’s formal letter requesting the adoption of 'Iran' in foreign usage.

British bureaucrats may have scoffed. Philosophers may misread it. But for Iranians, the renaming was a moment of clarity in a century of upheaval. As one British official grudgingly admitted in 1935, “a country can presumably choose the name it wishes to be addressed by.”

Reza Shah did just that. And nearly a century later, the name “Iran” remains a testament to that enduring choice.

Handwritten annotation expressing frustration with the Persian naming sensitivity.

Reza Shah was the first Iranian monarch in over 1,400 years to publicly honor the Jewish faith. During a visit to the Jewish community of Isfahan, he paid his respects by bowing before the Torah—a gesture that deeply moved the community and elevated their sense of belonging. For many Iranian Jews, this act secured Reza Shah’s place in their memory as the most respectful ruler toward their faith since Cyrus the Great.

A Final Note: Sardari and the Moral Identity of Iran

As debate continues over the geopolitical motives behind Iran’s renaming, it is worth remembering the actions of Abdol Hossein Sardari, an Iranian diplomat in Paris during World War II. Known as “the Iranian Schindler,” Sardari used his position at the Iranian consulate to issue hundreds of Iranian passports—many of them to non-Iranian Jews—enabling them to escape Nazi persecution.

He argued successfully that Iranian Jews were of Aryan descent and thus not subject to Nazi racial laws. Quietly and without fanfare, he saved lives at great personal risk, refusing to abandon his post even as Allied forces approached. Sardari’s actions were never sanctioned by Tehran; they were born of personal conviction and cultural values.

His bravery stands in stark contrast to the notion that Reza Shah’s Iran was ideologically aligned with Hitler. Sardari’s story, long overshadowed by larger geopolitical narratives, offers a final and fitting reminder: the identity Iran asserted in 1935 was not one of complicity, but of sovereignty—and, when it mattered most, of conscience.