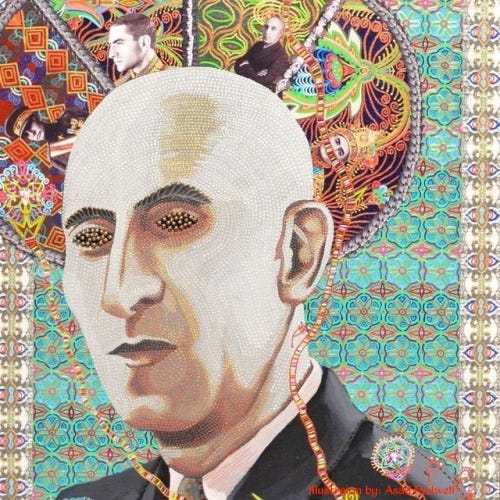

For decades, the name Mohammad Mossadegh has been mythologized in the Western press and among some Iranian intellectual circles as the avatar of Iranian democracy—a lone, aged warrior who stood up to the British Empire and was unjustly toppled by a CIA-backed coup in 1953. But scratch beneath the surface of this narrative, and a far more complex, less romantic, and often damning picture of Mossadegh emerges: a privileged Qajar prince, a feudal aristocrat with close clerical ties, who betrayed allies, crushed dissent, and undermined Iran’s constitutional system for his own ambitions.

Mossadegh: The Aristocrat Masquerading as a Democrat

Far from being a man of the people, Mohammad Mossadegh Ol’Saltaneh (Ol'saltaneh meaning "of the monarch," a prevalent Qajar princely title) was born into the ruling Qajar dynasty—one of the so-called "One Thousand Families" that dominated Iran for centuries. A feudal landlord and prince, Mossadegh enjoyed the fruits of privilege while claiming to represent popular interests. Contrary to popular Western narrative of having been “democratically elected by the people,” his appointment to prime minister in 1951 was through parliamentary maneuvering and royal approval by the Shah.

According to archival records and the unimpeachable work of Ray Takeyh, Mossadegh “represented not a democratic movement but a coalition of feudal landlords, religious conservatives, and small-time merchants” who feared the modernizing tendencies of Reza Shah and his son. In essence, he was the elite pretending to speak for the masses while safeguarding aristocratic and clerical interests.

The National Front: Origins and Opportunism

The political vehicle Mossadegh helped to forge was the Jebhe-ye Melli or National Front—a loose confederation of secular liberals, bazaar merchants, nationalists, clerics, and even some moderate leftists. Founded in 1949 as a coalition to challenge foreign oil domination and advocate for national sovereignty, it quickly devolved into a fragile and unstable alliance riddled with contradictions. While its public rhetoric was one of constitutionalism and nationalism, its inner workings reflected the compromises of its diverse factions—including those with deep hostility to modern reforms.

Mossadegh's leadership within the National Front was less about coherent ideology than personal magnetism and symbolic capital. He presented himself as a bulwark against both foreign exploitation and royal absolutism but often maneuvered behind the scenes to consolidate power and suppress dissent within the coalition itself. Though initially seen as a unifying figure, his failure to mediate between the secular and theocratic wings of the Front ultimately led to fragmentation. When Ayatollah Kashani and other clerical allies defected, the National Front began to unravel—leaving Mossadegh politically exposed and increasingly authoritarian in his methods.

Betrayals, Backstabbing, and Dowlatshahi

One of Mossadegh’s most consequential betrayals, as clearly explained in Manda Zand Ervin’s book, The Ladies’ Secret Society, was that of his cousin, Mehrangeez Dowlatshahi, a pioneering feminist, lawmaker, and future ambassador. As described in the rich accounts preserved in Iranian women’s archives, Dowlatshahi had secured support from women’s groups across the country for Mossadegh, promising that he would support legislation on women’s rights and enfranchisement. She believed she could help bring women into the political fold under Mossadegh’s leadership.

But Mossadegh turned his back on her and the women’s movement. He not only refused to support universal suffrage but, under pressure from clerics—particularly his close ally Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani—struck the women’s electoral clause from proposed reforms entirely. He had taken the support of women reformers and handed it to their enemies.

The Puppet of Ayatollah Kashani

Mossadegh and firebrand Ayatollah Kashani

Mossadegh's alliance with Ayatollah Kashani was perhaps the most revealing and damaging of all. Kashani—a hardline Shi’a cleric with a violent record of inciting mob violence—was brought into Mossadegh’s inner circle in order to bolster religious legitimacy for the National Front. Kashani's support ensured that Mossadegh had the street power to intimidate rivals, but it also meant making devastating concessions to theocrats.

The alliance enabled Kashani to become one of the most powerful figures in Iran, setting a dangerous precedent of mixing mosque and state that would pave the way for Khomeinism decades later. Mossadegh was more than complicit—he was instrumental. And when Kashani turned against him, Mossadegh lost his clerical shield and found himself politically isolated.

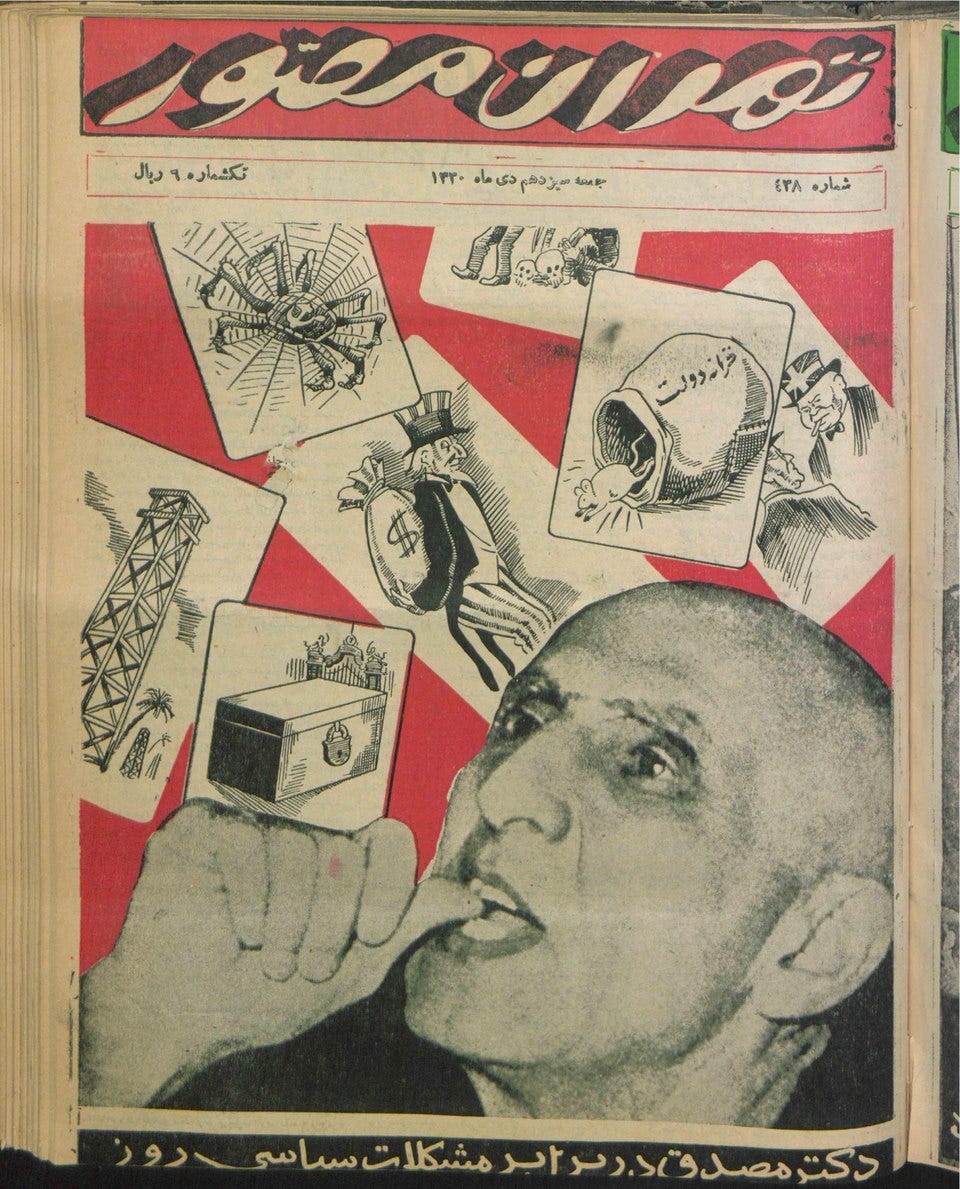

Anti-Constitutional Behavior: Dissolving the Majlis

Friday, January 4th, 1952 cover of Tehran Mossavvar Magazine describing Dr. Mossadegh’s reaction in the face of current political problems

Perhaps the most indefensible of Mossadegh’s actions was his decision to dissolve the Majlis (Parliament) and rule by emergency powers. The myth that he upheld constitutionalism collapses in light of this blatant power grab.

He sought and received sweeping authority from a Majlis stacked with supporters, then suspended its operations altogether when faced with dissent. Far from defending democracy, Mossadegh undermined it—relying on street mobs, often controlled by the Tudeh (Communist) Party, and his own emergency decrees. His government began to resemble a populist dictatorship rather than a constitutional republic.

In chapter 15 of her book, Zand Ervin notes, “While Prime Minister Mossadegh defended Iran’s rights and sovereignty at the International Court of Justice… The Soviet Union promoted communism and fomented unrest… Historical records show the British constantly pressured the Shah to fire his Prime Minister, which he refused to do”.

Courting the Communists and Alarm Among the Soviets

2 August 1953 - The Russian ambassador, Anatoly Lavrentiev, arrived in Tehran on 26 July and met with Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq, on 28 July and 2 August. Lavrentiev was sent to replace Ivan Sadchikov as ambassador to Iran. Mosaddeq’s last photo before the events of mid-August shows him conferring with the Soviet envoy. Photograph: Dr William Arthur Cram

Despite his aristocratic pedigree and supposed nationalist credentials, Mohammad Mossadegh permitted the Soviet-backed Tudeh Party to thrive under his premiership. The Tudeh—a militant, KGB-aligned communist organization—had a well-documented record of assassinating intellectuals, bombing police stations, and spreading anti-Western propaganda. Rather than confronting them, Mossadegh turned a blind eye, fearing that a crackdown would fracture his fragile coalition, which relied on the uneasy support of clerics, bazaaris, and leftists. Maryam Firouz, the so-called “Red Princess” and Mossadegh’s own cousin, often served as a go-between with the Tudeh leadership, further cementing suspicions of tacit coordination. This permissiveness allowed the communists to embed themselves deeply within Iran’s political fabric, destabilizing the state from within as the Cold War heated up.

Even Moscow grew uneasy. One often-overlooked dimension of the 1953 coup is the alarm it caused within the Soviet diplomatic mission in Tehran. Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Lavrentiev, reportedly disillusioned by Mossadegh’s erratic leadership and chaotic governance, is said—according to a contemporaneous New York Times report—to have attempted suicide in the midst of the crisis. Watching Mossadegh flirt with the Tudeh while failing to stabilize the country, Lavrentiev feared not only a Western-backed coup but the broader collapse of Soviet influence in the region. His despair underscored the wider international consensus: Mossadegh’s tenure was not the enlightened reign of a democratic reformer, but a geopolitical and ideological catastrophe that alienated allies across the Cold War spectrum.

American Support Was with Him—Until It Wasn’t

Mosaddegh with US President Truman, at the White House, in 1951

Another shattered myth is the notion that Mossadegh was abandoned by the United States. On the contrary, President Truman warmly welcomed Mossadegh to the U.S., offering him medical care and diplomatic support. Secretary of State Dean Acheson stood by him. It was only after Mossadegh began acting unconstitutionally, ignoring Parliament, and allowing Soviet sympathizers to flourish, that Washington grew concerned.

By 1953, the situation had deteriorated. Mossadegh had burned bridges with the Shah, alienated reformers like Dowlatshahi, infuriated the clergy, and stoked Cold War fears. When the CIA and MI6 finally backed his removal, he had very few friends left.

Ahmadabad: Self-Exile, Not Martyrdom

Today, Mossadegh’s house on his orchard in the town of Ahmadabad

When Mohammad Mossadegh was removed from power in August 1953, the reaction of the Iranian people was not one of widespread mourning or revolt, as so many Western accounts would later imply. The truth was far more nuanced—and damning for the myth.

After the coup on August 15—when Mossadegh forcefully resisted the Shah’s attempt to dismiss him from office—and the successful uprising on August 19 that toppled his government, Mossadegh did not stay and fight. He did not rally the people, call for a constitutional defense, or organize loyalists. Indeed, as observers on the scene remarked, the only people on the street willing to fight for him were the Communist Tudeh militants—not the ideal supporters for a proud former prince! Instead, the once-fiery orator and self-styled champion of Iranian sovereignty retreated to his family estate in Ahmadabad, an orchard near the village of Karaj. There, he lived quietly under house arrest, in comfort and security—not in a jail cell, not in torture, but among trees and servants, sipping tea.

Many Iranians saw this as a fitting end to a man who had postured as a patriot but ultimately failed to stand with the people when it mattered most. For women, intellectuals, modernists, and even many disillusioned clerics, Mossadegh’s fall was greeted with a complex mix of relief, frustration, and quiet vindication. He had betrayed their causes, empowered the wrong forces, and left the country weakened and chaotic.

Mossadegh’s resting place, inside his Ahmadabad house.

Indeed, by the time of his departure, Mossadegh’s support had eroded. He had alienated his former allies like Ayatollah Kashani, betrayed reformers like Mehrangez Dowlatshahi, and driven the country to the brink of economic collapse by refusing compromise during the oil crisis. In the minds of many Iranians—especially the rising middle class, women activists, and even young technocrats—Mossadegh was seen as an exhausted, aristocratic relic clinging to personal pride rather than offering a real vision for Iran’s future.

The Western Myth of Mossadegh & the Cultural Imperialism Behind It

And yet, despite the deep domestic disillusionment with Mohammad Mossadegh—across clerical, reformist, feminist, and technocratic ranks—the West, especially the United States and parts of Britain, have stubbornly sustained a romanticized narrative of him. Mossadegh is endlessly cast as the valiant democrat, the innocent victim of greedy oil barons and CIA intrigue. This tale has persisted for decades, repeated in academia, journalism, and pseudo-intellectual circles, even though declassified CIA documents from 1953 confirm—regardless of later bureaucratic claims—that the August 19 uprising was spontaneous and popular.

But why has this myth endured?

Because it serves multiple Western interests:

It absolves American guilt with minimal effort.

Reducing the fall of Mossadegh to a "CIA coup" orchestrated by the Dulles brothers and Kermit Roosevelt offers a morally convenient scapegoat. Western historians can wring their hands and say, “We made a mistake,” while avoiding the uncomfortable truth of Iran’s own internal political dysfunctions: Mossadegh’s aristocratic privilege, his reactionary alliances, and his undemocratic behavior.It promotes a cautionary tale against foreign intervention—while ignoring domestic tyranny.

Mossadegh becomes a case study in "what not to do" in foreign policy circles. But in spinning this parable, Western progressives and isolationists gloss over the real enemies of democracy in Iran: the entrenched clerical establishment, the Stalinist Tudeh Party, and the old-money aristocracy that Mossadegh embodied.It flatters liberal illusions of “good revolutions.”

The myth upholds the fantasy that Iran’s modern tragedy began with a CIA plot, and that had the U.S. not intervened, a secular, feminist, democratic Iran would have emerged. This is historical delusion. Mossadegh never championed women’s rights, pandered to Ayatollah Kashani, and shut down Parliament. He paved the ideological road for Khomeinism—not for democracy.

A key enabler of this revisionist fantasy is British author Christopher de Bellaigue. In his sentimental book Patriot of Persia, de Bellaigue offers a polished but deeply misleading portrait of Mossadegh as a tragic, noble liberal—a “man ahead of his time.” In truth, what de Bellaigue peddles is historical revisionism dressed in florid prose and coated in colonial nostalgia. His narrative is not grounded in critical historiography but in emotional convenience, crafted for a Western audience eager to believe that imperialist guilt is the root of all Middle Eastern failure.

This isn’t scholarship—it’s ideology. It’s an act of narrative laundering that flattens Iranian history into a cartoonish East-versus-West morality play. It ignores Mossadegh’s betrayal of women reformers, his alliances with regressive clerics, his authoritarian tendencies, and his willingness to risk national collapse rather than compromise. De Bellaigue and others like him participate in cultural imperialism by imposing a simplified Western redemption arc onto a nation with its own complex, indigenous political contradictions.

This myth of Mossadegh not only distorts the historical record; it undermines the genuine reformers, feminists, and modernists who tried to build a better Iran from within. It paints aristocratic feudalism and clerical appeasement as noble resistance—while condemning real secular modernization as imperialism.

It is time we call this for what it is: revisionist propaganda in service of Western moral vanity.

Who Benefits from the Myth?

This narrative serves both left-wing and isolationist factions in the West who want to blame U.S. interventionism for all global problems. It is useful to the Iran lobby in the U.S., including groups like NIAC, which push for appeasement policies by casting the Islamic Republic as an inevitable reaction to American “aggression.”

It also helps the Islamic Republic itself. By presenting 1953 as the “original sin” of U.S.-Iran relations, the regime shifts blame for its theocracy, repression, and brutality onto foreign forces rather than its own ideologically totalitarian roots. Khamenei regularly invokes 1953 not because he admires Mossadegh—but because the myth deflects from 1979.

The Damage to Iranian Modern History

The greatest victim of the Mossadegh myth has been Iranian historical clarity. The myth has:

Obscured the role of women like Dowlatshahi, Sadigheh Dolatabadi, and Senator Mehrangez Manuchehrian who fought for real democratic change while Mossadegh pandered to the clergy.

Ignored the agency of Iranians themselves, as though they had no internal conflicts, factions, or ideology—just helpless pawns of the CIA.

Sanitized clerical power, forgetting how figures like Ayatollah Kashani used Mossadegh as a puppet and then helped create the blueprint for the Islamic Republic.

Erased the Shah’s modernizing policies, which after 1953 led to women’s suffrage, land reform, industrialization, and massive increases in literacy and infrastructure.

Most dangerously, the myth de-legitimizes secular modernization by making it synonymous with imperialism, while painting clerical alliances and autocratic rule as somehow more “authentic.”

Iran’s Real Struggle is With Itself

Mossadegh is not Iran’s George Washington. He is Iran’s Don Quixote—tilting at windmills while the country around him burned. A privileged Qajar prince who failed to deliver democracy, who empowered its enemies, and who retreated when things got difficult.

If Iran is ever to reclaim its modern, sovereign, democratic identity, it must bury the false idol of Mossadegh and instead honor the true modernizers—women activists, secular reformers, and those who paid with their lives to build a future free from both clerical tyranny and foreign manipulation.

The truth is not romantic. But it is necessary.